One needs to repeat that what in Zionism served the no doubt fully justified ends of Jewish tradition, saving the Jews as a people from homelessness and anti-Semitism, and restoring them to nationhood, also collaborated with those aspects of the dominant Western culture (in which Zionism exclusively and institutionally lived) making it possible for Europeans to view non-Europeans as inferior, marginal, and irrelevant. For the Palestinian Arab, therefor, it is the collaboration that has counted, not by any means the fulfillment of Jewish nationalism.

– Edward Said, Zionism From the Standpoint of Its Victims, 1979

Part I: Off the bus

The bus rocks back and forth in stop and go traffic. I look out the window. Limestone and concrete housing developments hug the hills west of Jerusalem, towering over Bedouin camps below, marked by goat herds and tattered tarps. I walk down the aisle to where our trip leader is.

“I’m not going to Ma’ale Adumim,” I tell my teacher.

Watching the tour bus lurch on toward one of the most problematic West Bank settlements, I realized something was wrong. My high school classmates were progressive and politically active, yet only three of us stood together on the sidewalk.

—

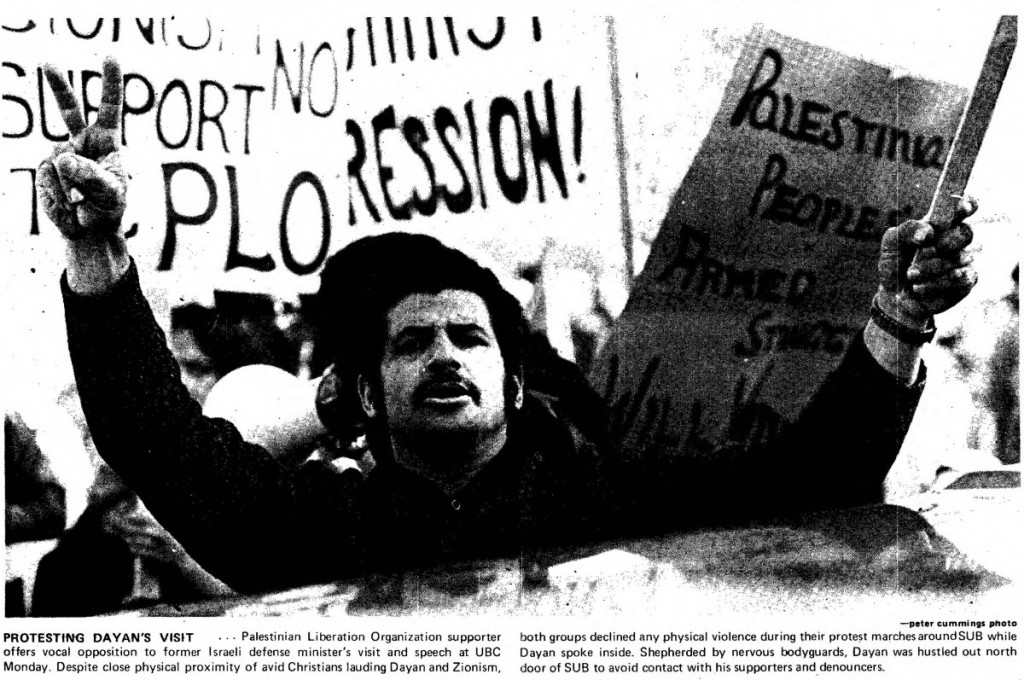

The Ubyssey covers the protests against former Israeli general and defense minister Moshe Dayan’s visit to campus in 1975.

Palestinian activism has crystallized around the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement, with dozens of student councils across North America, nine in Canada, passing divestment resolutions targeting Israel. I have followed these BDS debates both as a correspondent for a Jewish news service and as a Jewish student with friends on many of the campuses. I have noticed that while Jews have long held prominent roles in left movements and continue to identify with marginalized groups, Palestinian solidarity activism features a bipolarity that alienates many progressive Jewish students.

With the divestment debate at UBC, I am arguing for a broader Palestinian movement capable of attracting progressive Jewish students. By illustrating Jewish students’ fear of Palestinian activism and contextualizing their support for Zionism and Israel, I hope activists can erode the needless causes of Jewish alienation present in the movement. Mainstream Jewish and Palestinian groups joining forces to support Palestinian human rights and end the systemic oppression behind the conflict would make impossible for rightist groups to paint such activism as anti-Semitic and divisive.

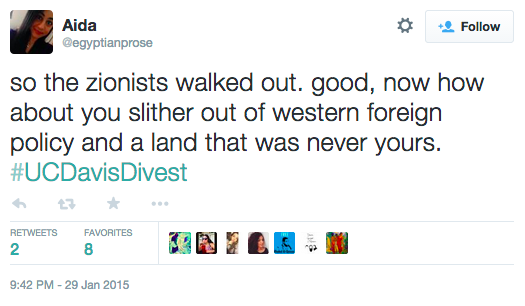

When anti-Zionists attacks feature anti-Jewish stereotypes, such devious snakes unduly influencing foreign governments, even Jews ambivalent about supporting Israel feel the BDS movement is no place for them.

Activists concerned about alienation primarily focus on separating Jews and Judaism from Zionists and Zionism, yet most Jews are sympathetic to Zionism and eroding Jewish alienation from the Palestinian cause requires ending the demonization of the ideology. Accepting Zionism may be a hard for those embedded in the Palestinian struggle or raised in Arab or Muslim communities. But Zionism, like Israel, means different things to different people.

Palestinian blogger Abir Kopty explains how many Palestinian activists, especially those personally impacted by Israeli actions, see Zionism:

Zionists are part of a colonialist ideology and movement that operates through institutions. Make no mistake. It’s not a vague term. It’s an ideology that has committed crimes against Palestinians and continues to inherently give Jews elite privileges over Palestinians, whether inside Israel, or in the West Bank — including East Jerusalem — and Gaza. Even in Exile.

While Kopty’s Zionism describes the lived experience of millions of Palestinians, it is entirely divorced from the Zionism embraced by diaspora Jewish students who are largely unaware of the detrimental effect of the Israeli state on Palestinians. Whereas British imperialism involved a “civilizing” mission and Afrikaner nationalism had anti-black racism baked into its core, the vast majority of Jewish nationalists – people who had no role in the founding of the state – seek only security and national redemption. Zionists are not “impossible to coexist with,” as a student senator at the University of California, Davis declared at a January BDS debate. Writing in 1978, Palestinian scholar Edward Said explained that it wasn’t the desire for self-determination – what attracts most Jews to Zionism – but rather the ideology’s collaboration with European racism, that drives the violence and dispossession many associate with Zionism, the implementation of which did not require significant dispossession. “For the Palestinian Arab, therefore, it is the collaboration that has counted, not by any means the fulfillment of Jewish nationalism.” In fact, Said robustly defended Jewish attraction to their brand of nationalism – writing that Zionism “served the no doubt fully justified ends of Jewish tradition, saving the Jews as a people from homelessness and anti-Semitism, and restoring them to nationhood.” But thirty-seven years after Said wrote that article, with Israel having grown in strength and the occupation becoming more deeply entrenched, it is easy to conflate attraction to Zionism for its virtuous features with support for its collaboration with an oppressive Western ideology, a union that most Jews are entirely ignorant of. But overlooking contrasting perceptions of Zionism, not based on different values but often on entirely different facts, leads to a binary framework wherein Zionism is all bad and its adherents best shunned.

My goal in explaining mainstream Jewish perceptions of Zionism is to challenge the assumptions those on the Left have about “Zionists” with the hope that doing so will make progressive Jewish students more receptive to Palestinian activism at UBC and elsewhere. “Zionists” should be part of the Palestinian struggle and allowing them in would not only attract many more Jewish students but also neutral observers at UBC and elsewhere scared off by the issue’s divisiveness.

Part II: Liberation Zionism

Israeli paratroopers at the Western Wall following the fall of Jerusalem during the Six Day War of 1967. Photo: IDF Archives

VII.

Zionism bases itself on three claims: (1) that the ancient Hebrews possessed ancient Palestine and nobody else lived there; (2) that modern descendants of European converts to Judaism are the direct descendants of the Hebrews; and (3) that, based on these two claims, modern European Jews have the right to take Palestine from the Palestinians.

VIII.

Religious and secular Zionists use the Jewish scriptures to assert that God promised the ancient Hebrews the land of Palestine and that the Hebrews went there and killed the native Canaanites and took their country. They add that this gives modern European Jews the right to repeat that very same crime today by killing the native Palestinians and by taking away their country.

These excerpts from Joseph Massad’s “Theses on Zionism” outline a standard anti-Zionist understanding of Zionism. But most Jewish UBC student don’t use Massad’s reasoning to defend their attachment to Israel. For Jews, Zionism is a political liberation movement and the expression of Jewish consciousness. Understanding this is essential to garnering widespread Jewish support for divestment at UBC and for the Palestinian cause generally.

Decolonial scholars led by Walter Mignolo argue the advent of Western imperialism led to the “the idea of ‘race,’ a supposedly different biological structure that placed some in a natural situation of inferiority to the others.” Taken with the emerging bourgeoisie’s replacement of Europe’s kingdoms with nation-states, this reordering of humanity transformed Jews from inferior in religion to inferior in humanity. Starting in the sixteenth-century, Jews became Europe’s internal colonial subject and were oppressed accordingly.

Theodor Herzl’s most enthusiastic supporters, the earliest Jewish settlers in Ottoman Palestine, came from Eastern Europe where Jewish communities faced regular violence and taxation intended to keep them in a destitute state, much like hut taxes in African colonies. By the time Herzl began peddling his message, European Jews had spent centuries living under discriminatory laws, violent pogroms and dehumanizing public rhetoric. Shut out from many industries, some Jews turned to professional fields like medicine, law and finance leaving the impoverished Jewish majority vulnerable to mass killings and rape by the resentful European masses. Zionism offered not just physical sanctuary but a chance to be proudly Jewish.

Max Nordau’s term “Jewry of muscle” captures the Jewish attraction to settling in Ottoman Palestine. A project of national redemption in the ancient Jewish homeland, embedded in Jewish culture for millennia, Zionism offered a new conception of Jewish peoplehood – a break from the internalized anti-Jewish racism embedded in the communal identity of European Jewry.

In 1942, early Hebrew novelist Haim Hazaz captured this concept in story where the protagonist, living on pre-state kibbutz, declares his “opposition to Jewish history,” demonstrating both the internalized racism of European Jews settling in Palestine and their attempts to move beyond it:

Jewish history is dull, uninteresting. It has no glory or action, no heroes and conquerors, no rulers and masters of their fate, just a collection of wounded, hunted, groaning and wailing wretches, always begging for mercy… I would simply forbid teaching our children Jewish history. Why the devil teach them about their ancestors’ shame? I would just say to them: ‘Boys, from the day we were driven out from our land we’ve been a people without a history. Class dismissed. Go out and play football….’

Right: An anti-Semitic pamphlet shows the tradition European view of Jews as physically diminutive and repulsive. Left: A propaganda poster illustrates the image of the new Jew offered by Zionism.

In 1948, the foundation of Israel juxtaposed with the greatest tragedy in Jewish history turned Zionism from a divisive issue among Jews to a point of pride. The 1967 war gave form to the new communal identity when Jews realized that for the first time in modern history they were essentially secure on par with other powerful nations.

—

Palestinian refugees stream out of Ramle, expelled by Israeli forces during the 1948 war. Photo: Government Press Office

That this narrative entirely ignores the damage wrought by liberation Zionism, the abstract idea that invigorated Jews around the world, once it morphed into applied Zionism is precisely my point.

Jews identify with liberation Zionism, not Kopty or Massad’s versions. Consciously or not, many Jews see Palestinian activism as an attempt to force them back to Hazaz’s era of Jewish “wailing wretches, always begging for mercy.” For the left to legitimize liberation Zionism by accepting that most young diaspora Jews – who often perceive a rosier vision of the Israeli state than even right-wing Israelis do – take pride in the new Jewish identity and security offered by Israel, and that this attraction is not inherently racist, is enough to open many progressive Jews on campus to the Palestinian cause.

Part III: In targeting Jewish liberation, missing Western oppression

A narrow focus on Israel can lead to progressive activists targeting Jewish liberation and nationalism while missing the broader Western forces of oppression that have become embedded in Israeli state actions. Here, JP Morgan Chase CEO James Dimon looks on as Israeli prime minister speaks at the 2009 World Economic Forum. Photo: WEF/Creative Commons License

The political environment in which Zionism emerged led it to reproduce the same oppression Europe visited on populations around the world in Palestine. While early Zionists answered to to no physical metropole, they were beholden to an ideological one.

Zionism used settler-colonial tactics to craft a modern nation-state, a recklessly exported European invention. In a blistering critique of the model, Mignolo offers a convincing explanation for Israeli oppression by arguing the premise of national sovereignty leads to dehumanization.

“Dehumanization is irrelevant in modern/colonial international relations: first comes state interest, second, the benefit of the citizens of the state who enact the dispossession [of non-nationals] and, third, the non-nationals being dispossessed,” he writes.

Israeli soldiers committed over a dozen massacres in Arab villages during the 1948 war, precipitating the exodus of many more. Since 1967, Israeli policies like the matrix of control in West Bank and Gaza indicate the absolute prioritization of Jewish Israelis at the expense of Palestinian rights, leading to the cavalier attitudes toward, for example, the killing of hundreds of Palestinian civilians in Gaza during military campaigns against Hamas.

But Israel is not exceptional. The logic behind its oppression is the same underlying all forms Western oppression – essentially prioritizing one class of nationals to better meet liberal economic interests. Zionism is not inherently problematic. Simply, generating progressive liberation movements within oppressive societies, as nineteenth-century Europe was, is hard; contemporary scholarship has skewered early twentieth-century African-American nationalism for likewise adhering to the European imperialism it was intended to overcome.

Israeli state oppression does not primarily benefit the Jews who identify with Zionism. As James Baldwin wrote, “the state of Israel was not created for the salvation of the Jews; it was created for the salvation of the Western interests.” Spotlighting it as a nation apart distracts from the systems of oppression governing Israel’s actions. It is “very overt, obvious colonialism,” UBC sociologist Rima Wilkes said of Israel in a 2013 interview. “Other cases are less overt, less obvious. Why isn’t there an American Empire Week?” Given Jews’ historical role as scapegoats, many Jewish college students question the emphasis on Israel. Jews have long been used to carry out the dirty work of oppressors; Western interests and colonial legacy drive Israeli state oppression, not Jewish nationalism – defined as the quest for Jewish self-determination – or its adherents. An orientation toward that distinction – for one, Israel should not be only state targeted with an AMS boycott – would both broaden the activism and allay Jewish fears (UC Berkeley recently passed a resolution calling for divestment from nine countries including Israel). It would clarify that it is the abuses of the Western worldview being targeted.

Part IV: Beyond the River to the Sea

Despite occasional violence, pronounced, competing nationalisms coexisted in relative harmony under the British Mandate. Here Jews and Arabs wait for the bus in Jaffa. Photo: Government Press Office

A visible shift at UBC away from attacking Israel and Zionism as unique and toward undoing the systemic oppression they express will allow a more inclusive struggle, avoiding the pitfalls of such activism elsewhere. For example, the accusations of dual-loyalty at UCLA – “Given that you are a Jewish student and very active in the Jewish community, how do you see yourself being able to maintain an unbiased view?” a student councillor asked a Jewish nominee to the judicial board – came just weeks after a swastika was drawn on a Jewish fraternity house at UC Davis following a BDS vote. The more Jews and Palestinians, two oppressed and marginalized groups – granted, not in the Israeli context but throughout the world – fight each other, the safer are the forces of Western imperialism that lie behind those abuses. Acceptance of Jewish identification with liberation Zionism will encourage identity to fade into the periphery, draw in more Jewish supporters and allow a clear focus on the systemic forces of oppression at hand.

The BDS movement demands an end to Israeli occupation of “Arab lands,” equal rights for Arab-Israeli citizens and the right of return for Palestinian refugees. BDS’ support on the left suggests its goals figure centrally in the worldwide fight against oppression. But there is a feeling among Jews who identify with Israel and Zionism that the divestment movement and Palestinian activism in the diaspora is oriented first toward attacking Israel and promoting, intentionally or not, the interests of Arab nationalist and Islamist political groups which often contradict the progressive values of Palestinian solidarity activists in the diaspora. Unless one believes Israel is the only oppressive actor in the conflict, the narrow focus of the Palestinian struggle on Jewish nationalism is hard to explain. If instead the argument is that given the immense suffering of Palestinians, practical concerns prevail, the narrow focus on the Israeli state is likewise hard to explain and especially glaring for Jewish observers.

Predicated on a supposed dichotomy between Israeli/Zionist oppressors and oppressed Palestinians, this alienating binary is reinforced by the anti-normalization stance of most Palestinian solidarity student groups whereby they often refuse to work with any organization that does not accept the BDS demands. The policy leads to an erasure of nuance and ambiguity in the oppression Palestinian activists seek to fight, with former SPHR-UBC president Shaban describing it to me as akin to the refusal of Jews to meet with the Nazis during World War II.

Palestinians have been one of the most politically manipulated groups in modern history. Their tragedy largely stems from Israeli and Western actions but has been compounded by Arab states’ reliance on the propaganda power offered by the festering conflict. While groups like the Popular Liberation Front for Palestine call for overthrowing of Arab regimes and most Palestinian activists recognize the role of actors besides Israel, when the Jewish state is the sole target in campus activism like BDS it presents a distorted view to those unfamiliar with the struggle. Shifting away from a binary that primarily or exclusively condemns Israel and Jewish nationalism will draw more supporters to the fight against oppression of the Palestinians and the other modes of oppression in the conflict.

Intersectionality demands of feminism that it acknowledge the wider spectrum of societal oppression besides that due to gender. Likewise, one can fight Israel for its abuse of the Palestinians living under its control, regional Arab states for their mistreatment of Palestinian refugees, Palestinian leadership for their abuse of populations they control, Palestinian and Arab militants for their attacks aimed at Jewish and Israeli civilians and violent Western foreign policy driven by selfish interests, without equating these modes of oppression or minimizing the centrality of Israel and the West’s role.

A broader struggle would also allow, for example, the incorporation of groups like the Mizrahim, Arab Jews who have faced decades discrimination by the Ashkenazi elite in Israel and, earlier, Arab governments. Arab-Jewish activist Loolwa Khazoom, writes, “I feel anyone who is pro-Arab out of the positive spirit of defending justice will embrace the Mizrahi reality. After all, the two are not in competition; and in fact, there are a number of places where they overlap.” Jamal Zahalka, chairman of the Israeli Arab nationalist Balad party, acknowledged as much, saying, “We totally miss the Jewish public, and this is one of Balad’s failures. We did not build enough bridges with the Jewish public that is open, at least partially, to the things we are saying.”

A move away from the current binary would clarify for Jewish students how Palestinian activists decide where to expend energy. For example, one can agree the Palestinian leadership in Gaza’s declaration that Jews cannot remain anywhere in Israel/Palestine is unacceptable. However, aiding a Palestinian population that cannot move freely, that is not treated as first-class citizens at home or in many places abroad due both to nation of origin, ethnicity and skin color, and whom the Israeli state is dedicated to keeping under tight control through violent and unjust measures is a higher priority than the theoretical plans of a weak Gazan government.

But if we stick with a binary that resists condemnation of non-Israeli or non-Zionist actors the popular notion among Jewish students that this is a debate about who should get to control the region, not a fight for justice, will persist. A visible shift from solely attacking the Israeli state and its supporters to include more forms of oppression in the conflict will make it clear the movement is not just focused on tearing down Israel, opening Jews to accepting the ways in which they are contextually privileged in the conflict.

Moving away from the binary would allow a restoration of humanity across traditional conflict lines, something that anti-normalization policies explicitly block and which Frantz Fanon argued in Black Skin, White Masks should be a key goal of decolonial movements:

Superiority? Inferiority?

Why not the quite simple attempt to touch the other, to feel the other, to explain the other to myself?

The occupation needs to end. The settlers need to leave the West bank; some need to be jailed. Anti-Arab racism and violence in Israel needs to end. Israeli leaders need to engage the Palestinians from a place of honesty. The fight against Hamas and other security threats needs to go beyond violent shows of force. Mainstream Jewish organizations need to direct more resources toward ending Israeli human rights abuses. These issues are the priority, not Palestinian acceptance of liberation Zionism, not an end to racist rhetoric by Palestinian leadership, not calls for boycotting, say, Jordan or Lebanon.

But to the extent Palestinian and left activism addresses the conflict’s ideological framework, like Israel’s settler-colonial roots, much can be achieved by legitimizing Jewish attraction to liberation Zionism. If liberation Zionists join the struggle, they are likely to see the problems inherent in a sovereign Jewish state. Perhaps they will find an anti-Zionist ideology that ensures a secure Jewish future or perhaps their Zionism will remain intact and when the time comes to negotiate the right of return or a binational state you will have comrades who can bridge the gap between hardline Israeli and Palestinian nationalists.

In 1945 the labor Zionist movement Hashomer Hatzair called for a binational Palestine. Perhaps their call can still resonate with those fighting for change:

[A binational solution] cannot hope to be carried into effect if Jews, Arabs and British alike each persist in maintaining that they have always been right while only the others were in the wrong. A thorough heart-searching on the part of all concerned is what is needed. Previous mistakes should be acknowledged… We hope that faith in humanity, in the better qualities of mankind, in progress and the victory of the masses will be the inspiring force in the solution of this grave problem.

By pitting two strictly defined national groups against one another in the tiny sliver of land that is Israel/Palestine we continue to operate in the European nation-state framework that dehumanizes populations and enables violent conflict. Solely targeting Israel and its Zionist supporters seems like an easy way to fight colonialism and earn liberation for an oppressed population, but it alienates progressive Jews and masks the deeper issues. By joining Jews and Palestinians together, not in supposed parity between the Israeli state and its Palestinian victims, but more broadly in the fight against systems of oppression that continue to affect both groups, the movement at UBC and elsewhere will not only be able to attract young progressive Jews – in other words, get the rest of my class of the bus – but will be far more likely to achieve true liberation for the Palestinians and other marginalized communities.

While the opinions expressed in this article are mine alone, I would like to thank those who challenged, questioned and helped clarify my arguments. Talia Gilbert, Elijah Jatovsky, Gordon Katic, Roshak Momtahen, Jude Al-Mukhalalaty, Talon editor Eviatar Bach and other members of the Talon editorial collective generously gave their time to make this article what it is and I am sincerely grateful to them and all others who assisted me.