Trigger warning: this article contains an intensely personal account of rape and sexual assault that occurred on the UBC campus. The article also discusses depression, self-harm and anxiety.

In February 2013, I was raped.

Like most people on the last day of Spring Break, I was at a party. Loud music, mixed drinks, dancing, talking, kissing, locked doors, darkness. Rape.

It took me six months to call it rape. It took me six months of depression, crippling anxiety and bloody razor blades to become aware of the fact that the events of February 22nd 2013 were not my doing. It wasn’t that I was wearing a low cut top, or that I’d had some wine or that I stayed behind to talk to him despite my friends’ warnings; it was that he took advantage of me. He was – he is – a rapist.

He doesn’t deserve more than a few sentences, but I am determined to note one thing about this experience. I knew him, just like 80% of survivors know the person who raped them. Not only did I know him, I trusted him. He was older, wiser, someone I had been convinced to trust. We were both scholarship students; both (supposedly) cherished by the University, both chosen from our high schools as leaders, and therefore both intricately entwined in each other’s lives. The heteronormative and hierarchical spheres in which we socialized led me to trust him. These spheres indoctrinated me to worship him as superior because of his age, his ‘trustworthy’ good looks, his traditional heterosexual appeal and his ‘harmless’ flirting. They held him as a god because of his excellent manliness, coupled with his academic success that the University loved so, so much. (What sort of person would say no to him?) These spheres – my friends, my peers, my advisors – were complicit in my rape.

My friends, all straight girls, downplayed experiences of harassment because our communities were focused around traditional relationship structures. Essentially, our conversations were centered around the ‘opposite’ sex, future husbands and potential mates. The men we knew insisted that “compliments are harmless,” “flirting is just a bit of fun” and “girls should lighten up.” I was nineteen, alone in Canada, and feeling like a freak because I didn’t have a boyfriend. So, I believed them. I believed them at the party, when my drink was being topped up. I believed them when the bathroom was inescapable. I believed them when my face was against the sink.

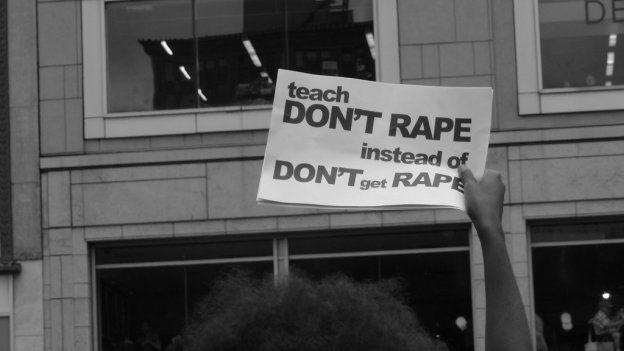

However, none of this erases the fact that there is only one person at fault here: the rapist. Never should the blame be removed from his shoulders and never should his actions be excusable. But we are all products of our society. I find no peace or closure in labelling him as a monster, as a sick and twisted individual, exempt from societal influences and acting alone in his crimes. Yes, he is all of those things and many more despicable adjectives — but he and I were both socialized such that this moment was inevitable. We had absorbed and inherited, throughout our lives, norms, customs and ideologies that caused him to be a rapist and me a victim. This does not mean that he did not make an active decision to commit a crime, or that his actions are in any way excusable. It means that our society has created a rape culture – one that is ripe with rape jokes, victim blaming, slut shaming. A culture that equalizes rape with success and acquits rapists – so that rape is inexorable.

Every seventeen minutes a woman in Canada is raped.

Four out of five female undergraduates in Canada have experienced violence in a relationship.

Half of all women in BC will be sexually assaulted in their lifetime.

Fifty percent.

That’s over a million women.

So he’s not abnormal. He’s just like the boyfriend/friend/brother/husband/colleague of 1 in 4 North American women. Not to mention he’s a Frat Boy: he’s 300% more likely to rape. And me? I’m a woman. My body is subject to legislation, sexualization, exotification, fetishization, objectification and correction, so it leads me to contemplate the expectations of a heteronormative rape culture such as this one. Our society has created the perfect platform for violation of female or feminized bodies, as it is founded upon patriarchy, violence, colonialism and the sexual power and privilege of cisgender heterosexual men.

I was convinced to see a counsellor. But I found UBC Counselling to be so conspicuous, so obvious, so terrifyingly close to student services like Enrolment Service Professionals and the careers center that I was afraid that I would run into someone I knew. The experience was troubling even before I sat in a dimly lit room with an older man who insisted on mis-remembering my name. The déjà vu was triggering. I decided to stick it out; I had to recover from my mental illnesses. I couldn’t bear the thought that not only had my body been violated, my mind had been broken too. Months of crying, insomnia and the inability to walk on campus without breaking into a paranoid sweat were just a few elements of the long term rape of my spirit. Not only was I struggling under the weight of social stigma against mental illness, I was crushed by the idea that these psychological burdens had been inflicted upon me. I found UBC Counselling neglectful and frustrating, from the long waits to the constant focus on my academic success rather than my overall well-being. However, the most triggering part of the experience was the counsellor’s insistence that I report the incident.

I didn’t want to report. I didn’t want to report because my rapist existed in so many of my social and academic circles. I imagined that the devastation caused by a court trial would destroy our tight-knit community and cause me to be alienated. What if no one believed me? What if I went through all the trauma of engaging with the racist, sexist, oppressive court system and he went unconvicted like 99% of rapists? What if his popular status, like that of Jian Ghomeshi, called people to support him and silence me? What if people assumed it could explain my queerness? What if people used it against me in feminist discourse? What if it discredited me in job prospects?

What if I had to relive the ordeal over and over and over again?

Support for survivors: