It seems counter intuitive to fly to South America to sit in a military installation to negotiate climate change action, but so it goes in the world of the United Nations Climate Change negotiation process.

As a delegate of the Youth Arctic Coalition and Polar Bears International I am following the 198 parties into negotiations in Lima this week for the week 20th meeting of parties (COP20). Their task is to prepare a draft text for Advancing the Durban Platform (ADP), a binding agreement to curb greenhouse gas emissions that may keep the planet from warming even further. As an advocate for arctic environments and self-determinism of its people amidst rapid change, my interest was to understand what makes these talks tick, why it has taken so long to reach a binding agreement and why this year matters more than years previous. As a graduate student in regional planning my aim was to understand the role of science in forming policy at the highest level.

The 5th report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change speaks to speed of Arctic change as, “mean Arctic sea-ice extent decreased over the period 1979 to 2012, with a rate that was very likely in the range 3.5 to 4.1% per decade. Arctic sea-ice extent has decreased in every season and in every successive decade since 1979, with the most rapid decrease in decadal mean extent in summer (high confidence)”. According to science, most of this sea ice change was caused by our consumption, industrializing, modernizing, flying around the world to climate talks etc.

Polar bears, reliant on a sea ice platforms to hunt in shallow waters, are not faring well either. Polar Bear International chief scientist Steven Amstrup has documented a decline in polar bear populations over time. A recent paper published in the Journal of Ecological Applications by fellow scientists notes, “we already see a decline in the body condition and total population of polar bears, especially in the South Beaufort Sea. At current trends, Arctic sea ice – will be nearly gone by 2100. By 2050, polar bears will likely be gone as well.”

Meanwhile, human settlements in the Arctic are already feeling the impact of shorter hunting seasons and a trending increase in extractive industry interest. Indigenous elders in Alaska have referred to the change as “a friend acting strangely.” Ice free summers have already yielded a three-fold increase in arctic shipping activity. Most adaptation projects in Arctic communities today focus on retaining the subsistence food livelihoods that remain and reducing the exposure to larger storm surges, higher seas and the potential contamination from a marine oil spill.

We understand what is at stake and why action at the highest political level matter, but entering the complex of circus-like tents, portable buildings and hundreds of negotiators from around the world in suits of all makes and models it is easy to lose sight.

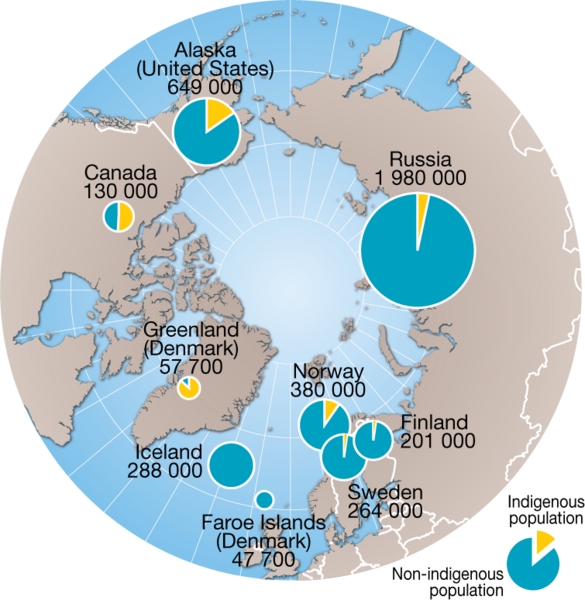

Entering a negotiation session is like taking a dive into an alphabet soup with acronyms like INDCS, LDS, SIDS and the ADP flying through the air. Lost yet? With dialogue focused on responsibilities of the developed (generally big greenhouse gas emitters) and the developing (generally low greenhouse gas emitters) world, it is hard to see where exactly the future Arctic is represented outside of its respective national and central governments. Do the hundreds of negotiators and organizations present know the rate of change that the Arctic’s 13 million residents and delicate sea ice habitats are undergoing?

Curbing the earth’s warming to 2 degrees centigrade is at the core of where science meets mitigation policy here. This is understood to be a threshold for ecological systems and even some built infrastructure. A unified effort to reduce emissions at this level will make major strides to keep polar bears around and reduce further risk in communities of the north.The goal for this summit is to have a draft binding agreement ready for COP 21 in Paris; this will have a positive impact on sea ice habitat and human settlements in Arctic regions.

While climate negotiations at this level have been ongoing for decades, it has has yet to produce any binding agreements. However, achieving a binding agreement at this level will set the tone at the highest scale and will reaffirm that nations around the world take climate change mitigation and action seriously. As of today, high level dialogues have begun. With China and the United States, the world’s biggest GHG emitters, at the table for the first time in years, ambitious action is possible. As now full rooms of negotiators, review and discuss documents, notably the ADP, line by line, make their positions known and critique words like [shall/should ]for hours, the pace is slow but hopefully steady.

As an NGO observer thus far, I have done a lot of watching, listening and learning. I have been able to offer a few small insights in climate adaptation working groups with the congress of indigenous peoples and Small Island Developing States namely around social vulnerability and UNDRIP best practices amidst climate change in coastal regions. Namely they are working to develop robust language around consent and human rights protection and impact in Advancing the Durban Platform (Mitigation) and the Nairobi Work Plan (Adaptation). Learning from these groups and watching the negotiations I hope to walk away with an understanding of how people find shared value and make good action policy.

At smaller scales, cities, researchers, designers, families and individuals can make major contributions to keeping polar regions cool, especially in the resource consuming global north. While I opted for a lift to Lima Peru in a 757 aircraft (last minute) over a multi-month bike tour (preferred) what I am learning is how policy is crafted and the power paradigms at play and how voices of the under-represented and often most impacted can be heard. It has been very informative. In a time of rapid change in the Arctic, active dialogue and a timely agreement at this level to curb warming and fund adaptation counts, even if it takes a flight.

Want to get involved? Sign our petition to protect addressed to UN Executive Secretary Figueres here.

This article originally appeared on the author’s blog.