This is part one of an interview series on The Knoll, a grassroots student press that was active on campus from 2006 to 2010. Former editors Nathan Crompton, Tristan Markle, and Bob Neubauer sat down with The Talon to talk about the original grassy knoll, real-estate development at UBC, the history of their activism on campus, and the radical origins of the New SUB

The Knoll newspaper began in response to the proposed development of an underground bus loop, shopping mall and new set of condos in the centre of campus (where the New SUB now stands). This proposed construction would tear up a popular green space for students, known plainly as the knoll. This is where the paper got it’s name.

The paper emerged in 2005 alongside a number of other critical student groups who organized around issues of campus development, social justice and environmentalism. A movement against the destruction of the UBC farm (which was set to be torn down to make way for condos) also sprang up around this time.

Rooted in an unapologetically leftist ideology, The Knoll dealt with more than just campus development. The publication was intensely critical of neoliberal politics and focused on situating campus ongoings in a broader campus context while demanding meaningful action from the AMS. From apocalyptic leftism to playful satire, The Knoll featured a variety of content that included essays, art, reviews and poetry. Several old issues of The Knoll can be found archived here.

Published with funding from the UBC Resource Groups, The Knoll was closely tied to several organizations on campus including the {{Students for a Democratic Society (SDS)}}[[Students for a Democratic Society (SDS)]]Students For a Democratic Society were a radical student group with the goal of to democratizing the university and all aspects of society[[Students for a Democratic Society (SDS)]], the {{UBC Social Justice Centre}}[[UBC Social Justice Centre]]The Social Justice Centre was and continues to be an AMS Resource Group that organizes around social justice issues and provides resources for activism on campus.[[UBC Social Justice Centre]], and the {{Trek Park Collective}}[[Trek Park Collective]]The Trek Park Collective was an open assembly focused on mobilizing students against gentrification and privatization in the centre of campus.[[Trek Park Collective]].

What’s most striking about the testimonies below is how completely this history has been erased from present-day understandings of the university. The contributions of student organizers are absent from the UBC narrative. The drawn-out and much-publicized naming of the New SUB, for instance, featured no discussion of the fight that brought it about in the first place. The collective loss of this history contributes to a belief that student politics are, and have always been, largely ineffectual and personalistic. The history of The Knoll, however, gestures towards something different.

Were you guys around for the original campaign to save the grassy knoll?

Bob: That was the reason I was involved. I was pretty much graduating and then you guys [Nathan and Tristan] circulated the petition. That was the catalyst for The Knoll newspaper and the consultations because you guys forced them to have actual consultations, and it brought about occupation of Trek Park.

Nathan: We overtook the parking lot outside the knoll for a good six months. It had been an actual functioning parking lot.

There were people living there?

Nathan: People spent some nights there. The site had a giant dome. Mostly it was about being in the space.

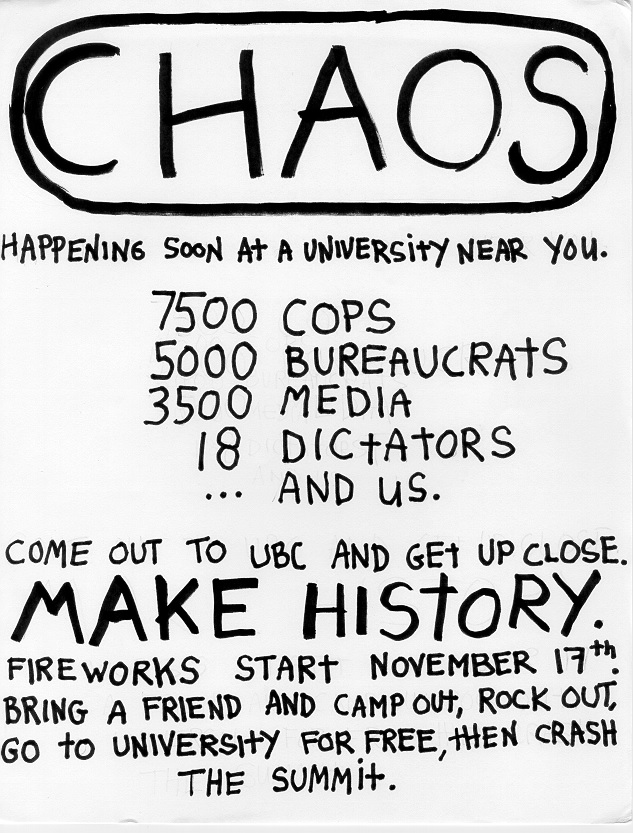

I think we should backtrack a little bit to set the scene, though. In order to position The Knoll I would go back to the late 90’s and, I guess, the the {{APEC protest}}[[APEC protest]]APEC, the Asia Pacific Economic Co-operation Conference, is an economic forum which promotes free-trade. The 1997 APEC Conference took place at UBC and was met by mass demonstrations. Police brutality against protesters was rampant and many were arrested.[[APEC protest]]. That’s where the Resource Groups came from, really.

We had a situation where students, {{APEC Alert}}[[APEC Alert]]An anti-APEC group composed of students, faculty, staff and others.[[APEC Alert]] and people from all over the city, including the Philippine Women Centre and Kalayaan Centre as well as different groups were working together. Their mobilization had an influence within the student society which ultimately led to the creation of the Resource Groups.

ABOVE: APEC ALERT POSTER FOR 1997 APEC SUMMIT PROTEST

Nathan: By the early 2000’s student politics was focused around the Iraq War. That was the biggest campus mobilization since APEC. With the invasion of Iraq you had all these new groups, and the Resource Groups were also being reactivated. By the time I got into the Resource Groups, anti-war politics were central.

Bob: it was pretty fundamental to actually politicizing a lot of the people that would eventually fight against development and join The Knoll.

Nathan: At a certain point {{M.A.W.O.}}[[M.A.W.O.]]Mobilization against War and Occupation, a controversial local leftist anti-war group[[M.A.W.O.]] overtakes the Social Justice Centre, which is important because you have this situation where we ACTUALLY couldn’t organize around anti-war issues for a good year.

Bob: They’re [M.A.W.O.] involved with a lot of different issues. They had a lot of different institutional bases. They essentially colonized certain issues – and I’m using that choice of words strategically -… anything to do with Cuba they’re there.

Creating the Students for A Democratic Society kind of came out of that. We created a place where, even though it was funded by the resource groups, they couldn’t just enter and outvote us.

M.A.W.O. kind of stopped the campus left in its tracks then…

Nathan: What it did was push us into other areas of organizing.

Bob: It was productive in a way

Nathan: What’s interesting is once we did start organizing around campus issues, campus democracy and tuition, suddenly the turnout was way bigger. The September [September 2007] that we started, we were having 50 people at meetings weekly. We were holding meetings at Trek Park. At the time the administration was rebranding around the {{Great Trek}}[[Great Trek]]The Great Trek was a student protest march that took place in 1922 as a response to the declining condition of UBC facilities and the provincial government’s slow progress on the construction of the Point Grey Campus. Re: the rebranding – the UBC Alumni Association, for example, publishes “The Trek” magazine, co-opting the name of the protest.[[Great Trek]].

Bob: The other piece of context is that around this time, the mid 2000’s, the story about UBC was that no one organized.

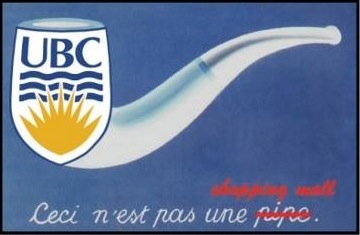

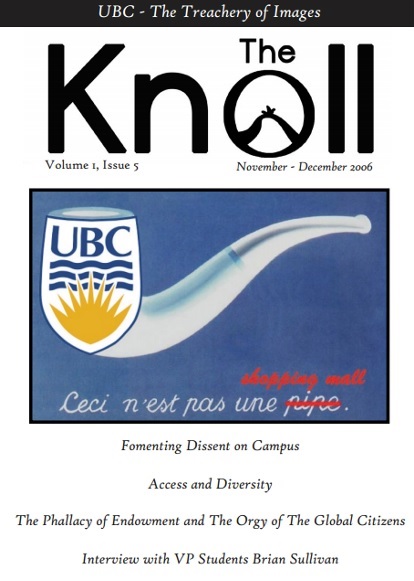

ABOVE: COVER OF KNOLL VOL 1 ISSUE 5 (Rene Magritte with help from: Tristan Markle Bahram Norouzi Mike Thicke)

But 19 people were arrested at ” Knoll Aid” later that year [April 2008], so obviously that changed drastically

Tristan: For a little bit of background let me say that Knoll Aid, and Trek Park – the whole movement – was quite fun. It was a joke, it was meant to be a party, a celebration. The reason it was called Knoll Aid was because Farm Ade had been going on for years. So it tied together the environmental struggle on south campus with the corporate one in the middle of campus. That’s why we called it Knoll Aid – it was like the centre campus version of Farm Ade.

The environmental activists and the social justice activists were completely united. That was really important.

Did anything come from the arrests?

Bob: It really hit the international students. Some people lost their degrees, or had a huge wrench put in the works.

Nathan: For the arrests there were two stages. First Stefanie Ratjen got arrested and we de-arrested Stef, then there was another guy who had also been arrested and was already in a cop car. It was harder to de-arrest him because he was in the car, but there were more people involved – maybe thirty people surrounding the car. It was very personal and they [the police] really came into our space and started arresting us, with no protocol and no de-escalation. There was around fifty cop cars; cars from all the way out in Richmond, they had called cars from five different municipalities

Tristan: Some context again – the first Knoll Aid was at the beginning of the year. And it was a popular movement all throughout the year, until the end of the year with the arrests. It started polarizing at some points, the frats got hostile in the spring. The two Knoll Aids were at the book ends. It was a celebration.

Nathan: Tristan put $800 worth of sod on his credit card, for the parking lot where it was held.

Tristan: We also got some trucks and went to where they were building condos on South Campus and stole their dirt [laughs]

Bob: We got electric screwdrivers and took apart the TransLink temporary bus shelter to get the plexiglass because hippies fucking love plexiglass domes. Hippies love geodesic domes. It reminds them of fractals for some reason. I have nothing against geodesic domes: if you’re going to live in a dome it might as well be geodesic. It was great because we disassembled everything, but hippies aren’t very punctual so we had this plexiglass sitting in the resource groups for months.

Bob: Then we had to get a table saw, we turned the whole resource group centre into a workshop to make this huge geodesic dome which became our base of operations. Until the frat boys really started to not like the dome. They would show up and piss in it at night, they would write open letters, they drove their truck into it! But it was tough dome.

Tristan: They drove their truck into it and it was literally caved in but we just went back the next morning and pushed it out.

Bob: And they sent us a letter telling us they would “smash up and piss in your offices too if you had any” but we were reading this letter in the resource centre which were our offices. And we were like, thank god these guys don’t know we have offices like 60 feet away from the dome [laughs].

Tristan: It was very funny. That’s what I’m trying to say… it was very funny. We had like 30 people inside the dome, people across the city knew about it. Journalists were coming. Journalists came and they would crawl into our dome and write about it: [in a serious journalist voice] “the students are inside the dome.”

Nathan: Can I raise some self-criticism about it though? I felt that the fun came from a lack of confidence, insecurity about our own politics.

Bob: Yeah people didn’t feel that they could be serious, or take themselves seriously

Nathan: Part of the reason I say that is because it was a very hostile environment to be organizing in. But we overcame that. Being into municipal politics now and thinking about the way in which we did frame issues of development, we always had a good analysis of it, it was always about control and profitability and the neoliberal university cashing in. But a self-criticism comes in for me in terms of the way the knoll [the physical grassy knoll] was picked up as an icon of the movement. There was often, around the counter-culture that we were immersed in, as opposed to the hard left elements in our movement, a kind of issue of sentimentality around the knoll. A lot of people thought we were sad the knoll was being dug up.

Bob: It’s almost like the situationist trap. I agree with that self-criticism. On one hand it was valuable for everyone to enjoy spending time with each other and for people to think that politics could be fun or interesting, but I do agree that it became a problem for optics eventually. The wacky knoll/dome escapades could often overshadow the actual issue of development at the university. That being said if it wasn’t fun at all it wouldn’t have been possible.

Part 2 of The Knoll interview series will focus on the subversion of development consultations on campus and the birth of the New SUB.