Content Warning: This piece is a personal account of depression, anxiety, and suicide in the context of contemporary student life.

If you or someone you know is having thoughts of suicide please call 1-800-SUICIDE (1-800-784-2433) or contact Vancouver Coastal Health’s SAFER services.

In the chaotic return to campus for the fall term, September 10th, Suicide Awareness Day, weighs heavy on my mind. I often find myself in uncomfortable staring contests with ominous posters and bus ads warning that ‘silence kills’. These always seem oddly out of place next to the influx of new and returning students bursting with life. It’s pretty easy to shudder and move on. Yet September 10th is an opportunity to reflect on how badly mental health awareness and support services are needed and how difficult and nuanced the conversations on these topics need to be. The detrimental effect of intersecting oppressions contributes to higher rates of suicide among queer, trans, and intersex people of colour (QTIPOC), people with disabilities, people facing class oppression, and racialized and Indigenous youth more broadly. Systematic and structural oppression can either deter these folks from accessing resources or greatly affect how they interact with pre-existing health care models. There have been countless think pieces on the correlation between intelligent high achievers struggling and feeling isolated and how millennials are deeply unhappy. In short, “we are a generation… who were told we could do anything and instead heard we had to be everything”1. There are far too many people caught in the silence and messy in-betweens.

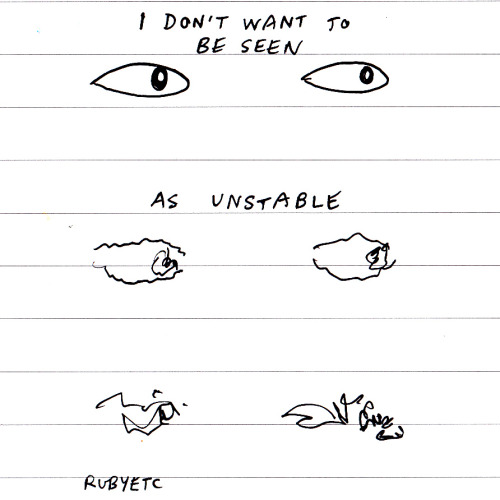

Years of looking at awareness campaigns urging their audience to speak up because silence is fatal has prompted me to ask: what does it mean to speak up and go public with personal histories of suicide? What does it look like for individuals to be publicly, openly mentally ill? Of course silence in the form of negligence, stigma, shame, and isolation are deadly combinations, but what does it cost individuals to tell their stories? I struggle with lifelong mental illness which includes, but is not limited to, depression and anxiety. Even anonymously, I am uncomfortable and too ashamed to share some of my other diagnoses. I am someone that struggles with suicidal ideation (suicidal thoughts), self-harming behaviours, and self-destructive tendencies. I thought very carefully about whether or not to put my name to this piece. Being anonymous feels too similar to hiding, and I am so very tired of hiding. However, I realised there could be negative implications of having my name publicly linked to mental illness and suicide. The reality of being publicly vulnerable is very challenging to navigate. I am fearful of not being in control of how people perceive me. It would be foolhardy to pretend that there is no longer stigma attached to mental illness and, particularly, suicide. Above all else, I desperately don’t want to be seen as unstable (see image above). Perhaps one day I will have some distance from the severity of my mental health struggles so I may own them more publicly. However, being on this journey of illness and recovery, and of hurting and healing, provides me with an opportunity to highlight the complexity of mediating function and disfunction. Many folks with mental illness do not get the luxury of choosing how others get to experience or find out about their illness. It must be noted that this ability to amplify my voice while retaining privacy is an immense privilege.

It is vital that discussions of suicide address the intermediary aspect of struggling with suicidal ideation, the challenges of (in)sufficient care for chronic illnesses, and the gaps in support services. We need to be seriously discussing what it looks like for people who are caught in between and don’t fit neatly into existing diagnoses and support services. Currently, our medical system has imperfect and outdated models for assessing folks who are struggling with suicidal ideation. We have a triage system that assesses if the person in question is immediately in danger of harming themselves or others. The most crucial question a suicidal patient is asked upon intake is if they have a plan. This timely, decisive model certainly has it uses, but it fails to take into account folks who routinely encounter suicidal ideation and tendencies. These services are necessary for crisis management — to keep people alive. Yet they are also reactionary and have a poor understanding of the multiplicity and complexity of suicidal ideation. They do not reward suicidal folks for being self aware and doing preventative work to keep themselves out of danger. To put it bluntly, when I am not doing well I am always thinking about how to kill myself. I am keenly aware of my self-destructiveness. I intentionally do not allow myself to formulate or enact any one plan. On the numerous occasions I have gone to the hospital when I felt I was a danger to myself, these attempts at self-preservation have limited how I have been able to access support. The message this gives suicidal folk who are doing their utmost to be reached, to foil their own plans, is that their reality isn’t worthy of services and care. Our intake services minimise the daily struggle of suicidal ideation and dissuade patients from determining how they access support. This serves to tell a desperate individual that they are a problem, which is a very dangerous and damaging setback. We need to be emphasizing that the services are lacking, not the person. Otherwise people who already feel burdensome are being told they continue to be problems. If you are told you are not sick enough or not presenting as sick enough in a specific, clinical moment it calls into question the choice to be seeking help in the first place. This minimization process is contagious and it becomes all too easy for high functioning mentally ill folks to get in the habit of dismissing their issues and doubting their judgement of the severity of their problems. I cannot count the number of times I have told someone I could not bear to be alive for one more day in the same breath that I have said I’m fine.

I’m fine I’m fine I’m fine. I have to be fine. It will be fine. It’s probably nothing. Don’t worry. I’ll handle it. It’s mine to fix. Forget I said anything.

I’m always fine until I’m not. I can’t count the times I have sought out hospital emergency rooms alone and eventually left without telling anyone because I couldn’t stand feeling so simultaneously in the way and invisible. I was scared by how easily I just got up and slipped out past the chaos. The last time I was in the hospital two friends came with me and held my hands the entire time. In the six hours we were there on a Saturday night every time I apologized and said it was a mistake to come they firmly and kindly said, “Oh, we’re not leaving”. For the first time I came away from the hospital having seen a psych doctor for assessment and with a clear picture of the services I could access and the waiting lists I would be put on. I am sharing this anecdote in an attempt to give insight into how disheartening and upsetting it is to navigate these services alone. Being mentally ill means continually having to advocate for yourself when you are at your worst. I often find myself walking out of specialist appointments I have waited on for months feeling lost and small and no further ahead than months prior, being condescendingly patted on the shoulder while the refrain of “You’re such an articulate, bright young lady, you’ll work it out” rings in my ears. I’m very good at minimizing my own issues. I don’t think that’s an accident and I don’t think that it is unique to me. This warrants further discussion about our health care services not least about how navigable these services are, who they best serve and who they alienate and dismiss. I have days where I just cannot be on subway platforms, days I don’t walk over bridges, days where I stay out walking for hours not trusting myself to go home until I am too exhausted to do anything but sleep. When I am not doing well my loved ones answer my phone calls with a panicked “are you safe?” by way of greeting. I am someone who calls a crisis line in the morning and writes an exam in the afternoon. We need to do more to recognize this complex reality so we can provide appropriate support for people who are struggling but passably functional.

When it comes to discussing mental illness and suicide in the context of campus it is important to reflect on what it means to promote balance and prioritize health. How meaningful are these conversations if the reality of adjusting ideas of personal success is unfeasible for those of us whose identities are too closely intertwined with academic excellence? I look at the last five years of my life and I honestly do not know how I’ve done it. I crashed and burned spectacularly in my second year and was able to scrape a term of medical Withdrawals (as a result of being registered with Access and Diversity) rather than Fails. Those W’s on my transcript bring tears to my eyes and I always ask myself why I didn’t persevere and complete the term. This is when I rely on my support network to remind me how bad things got. It was a very scary, confusing time for me that I hardly remember. I usually tell people that I ‘took some time off for myself’ because somehow it feels less shameful when I phrase it as a casual, mature choice. I don’t want people to know how difficult it is for me to take care of myself. I have been faced many times with distraught loved ones telling me to pause my degree and take less on. Though my health, happiness, and relationships have suffered immensely I have maintained an A average my entire degree. And for what? It’s been hell. I’m frightened to look back and see that time and again I willingly chose grades over my health. At the end of every term I turn to my best friend and laugh “well that nearly killed me.” She never laughs with me. It’s too real.

In academic communities and in classrooms we need to be talking about these serious and uncomfortable topics with the assumption that there are people in the room who may be currently struggling with mental illness. We cannot be further isolating folks by painting suicide and suicidal ideation as extreme, unlikely, and highly dysfunctional. Additionally, the flippancy of phrases such as “that makes me want to kill myself/shoot myself/slit my wrists” to express boredom, disgust, or frustration are extremely problematic in the ways they devalue and desensitize us to the language of suicidal ideation. The alarming frequency and nonchalance in which folks speak like this has real consequences. Not only is there a very high chance there is someone who overhears and is personally triggered, but it also means that people mustering the strength to share a personal secret and get help have to do that much more to be heard.

From my experiences being on both sides of mental illness (I have been in need of support and I have also played the role of supporter for close friends in dire situations) it is clear that our networks of support are precarious and unsustainable. Not because people aren’t loving and caring but because supporting a loved one with suicidal tendencies is draining and terrifying. Most people have the instinct to help but often feel powerless and frozen by a fear of making things worse. As a result many folks with chronic mental illness feel obliged to protect and care for the people in their support networks. This tense standoff means that no one is fulfilled in the role of helping and no one is getting adequate care. This can add heart wrenching emotional strain and resentment to previously healthy relationships. We cannot rely on the compassion and commitment of individual relationships to keep suicidal people safe. Individuals who are most empathetic and able to understand suicidal people often have these skills as a result of their own experiences. While there is something wonderful about finding other struggling folks and being able to recognize and validate that shared pain, this is bound up in complex levels of trauma.

Increasingly I have become uncomfortable with the glaring discrepancy between my willingness to offer support to my friends while dismissing my own value and failing to take my own advice. I like the role of supporter but I am quick to encourage peers and friends to use resources that I have felt too ashamed to access myself. I have felt disingenuous to be preaching self love and self acceptance while hurting, hiding, and disqualifying myself behind closed doors. I recently came across an Anais Nin quote that illuminated the complexity and duality of support networks. “I was always ashamed to take. So I gave. It was not a virtue. It was a disguise”. This is not to say that people who are struggling cannot simultaneously offer support, but it showcases how reliant networks of care are on particular people who are already overwhelmed. When it comes to personal boundaries regarding mental health it’s a ‘put your own oxygen mask on first’ kind of scenario. It is imperative that as members of communities in solidarity with one another we are invested in understanding each other’s needs and why they arise, even if we are unable to fathom experiencing them. I think it does a disservice to personal stories of pain and resilience when we tell people ‘put yourself in their shoes’. This implies that those shoes are easy to fill, easy to understand, temporary, and easy to leave. Anyone who struggles with invisible, chronic, and/or stigmatized illnesses knows that this is certainly far from the truth.

Although navigating resources can be discouraging, I have found that when there is space for vulnerability and sharing the potential for connecting to and healing with one another grows exponentially. It makes me unbearably sad that there are so many people in my life who have suffered immensely from mental illness and its complications. However, it is through being more open about my own issues that I have been able to make stronger, more meaningful connections to friends and strangers alike. As I have worked to better articulate my needs (in safe spaces to receptive people) I have been increasingly overwhelmed by positive interactions that have altered and accelerated the self care work I do. I am humbled by the intimacy of care and honesty that I have experienced when people I love and admire have chosen to sit in spaces of vulnerability and work to reach me. Making space for sharing stories and pain has made me feel that not only are my difficulties very real, but that the work I do to not be ruled by my illnesses does not go unnoticed. Slowly but surely these demonstrations of support and understanding accumulate. If a day goes by where I choose to be here and show up for myself rather than hurt myself, that is a victory. Every time I get approached by someone wanting to talk to me about mental health I feel like I am part of something productive and powerful. By witnessing and validating one another a gradual process of recognition occurs. If a loved one is more transparent about their struggles and this knowledge does not diminish my love for them, then in turn maybe I too am worthy of love and compassion. The healing intentions behind these connections have enabled me to recognize that maybe I too appear as strong, resilient, and capable as the friends that have shared their darkest secrets with me. Maybe I can start to recognize that the stories I tell myself about myself are a little outdated and a little tired. If I recognize the gap between how people negatively perceive themselves and how they appear to others, then maybe I am also wrong about myself. The more we see one another clearly the more we see ourselves clearly. At the end of the day, mental illness and the personal struggles it entails does not vanish magically, but the weight of this burden dissipates when shared. Being willing to have these conversations is about being willing to cultivate the tools we need to reach out and in turn be reached. It is about putting steps into place to plan and prepare to prevent isolation and desperation.

I must admit, I wanted this article to be perfect and poignant. I wanted it to provide all the answers and fix all the problems. But right now, I think I’m too close. The topics that I’m writing about are my reality. Writing this has been difficult and it has taken a lot out of me. It took far longer than I wanted it to because I had to close my laptop and walk away when it was too upsetting. I had to take my own advice and take care of myself first. I am in the midst of doing this work. I would by lying if I said it isn’t sad, boring, frustrating work but I would also be lying if I said it didn’t pay off. I can say that I no longer believe I am an inherently bad person who does not deserve a life, but I do continue to struggle with self destruction and suicidal ideation. I hope that this article broadens the conversations we are having in our communities and on campus about the reality of chronic mental illness, invisible illness, and suicide. To me, it is not about putting periods of illness and despair into tidy past-tense boxes, but instead lessening the impact of these struggles so that they become manageable background noise in full, vibrant lives. I’ll conclude with a sign off my best friend and I used to text each other in our darkest times.

“Be gentle with yourself. All the love. Call if you need.”

Special thanks to Jane, Mary, Anne, Eviatar, and K for their editing skills and compassionate support.

If you would like to speak to the author of this piece directly, email talonubc@gmail.com with the subject line ‘Suicide Awareness Article.’ Please be considerate of confidentiality and respect personal boundaries.