This article originally appeared on Rebel Youth: http://rebelyouth-magazine.blogspot.ca/

“The flame of Hikmet which set hearts on fire can not be extinguished, as long as there are people, militants, who will struggle to improve life and make it more beautiful.” – Dimitri Koutsoumpas, General Secretary of the Central Committee of the KKE at the Scientific Congress organized by the Greek Communist Party in honour of Nazim Hikmet, 13 June 2015

“One religion, one law, one right: the labour of the worker” – Nazim Hikmet

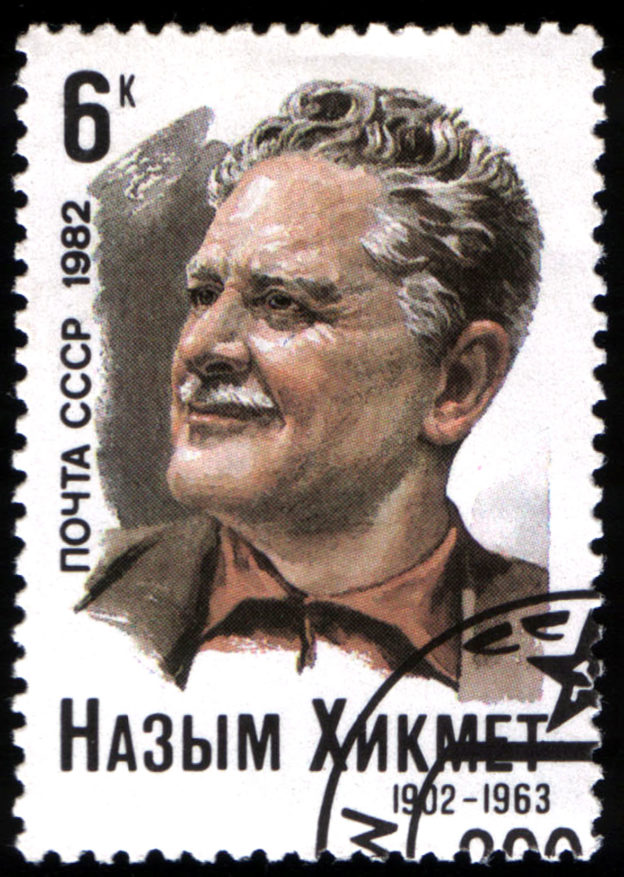

In an era when Turkey is more polarized than ever and the limited democratic institutions built there are are under attack, it becomes increasingly important for the Turkish left to recognize and reclaim their socialist legacy. There is perhaps no one figure more symbolic of that legacy and its silencing than the legendary poet, Nazim Hikmet Ran. Nazim Hikmet was born in the Ottoman Empire and would partake in the Turkish War of Independence in 1919. While his earliest poems written during those early years are nationalist rhetoric, his worldview would change significantly when he travelled to the Socialist Republic of Georgia in 1921. There, he witnessed firsthand the results of the Bolshevik Revolution, and as a result travelled to Moscow to study at the Communist University of the Toilers of the East. When he returned to Turkey, he brought with him both the Marxist-Leninist vision of social change, and the newly developing writing style of the young Soviet state, with particular influences from the Russian poets Vladimir Mayakovski and Vsevolod Meyerhold. However, while his convention-defying poetry was celebrated, his politics did not receive the same respect. Arrested, tried, and sentenced for the communist ideas expressed in his poems, Nazim Hikmet would spend long years in jail and finally flee to the Soviet Union, living the rest of his life in exile. Nazim Hikmet is considered the greatest poet of the modern Turkish language and his poems are taught throughout schools in Turkey. Yet, the very state that praises him also persecuted him, forced him to spend half his life in solitary confinement and the other half of it in exile in the Soviet Union for his communist views. Further degrading him, the Turkish government would repeal his citizenship, only reinstating it in 2006, fifty years after his death.

His poems were unique for his time. Until him, there was a distinct gap between literary and folk poetry in Turkey – the former being elitist in language, and both adhering to strict syllabic meters. Nazim Hikmet was the first to bridge this gap and the first to break free from metric conventions. His poetry is entirely in free verse and yet retains a certain lyrical flow. His poems are rightly lauded for their simplicity and accessibility, as well as their deep symbolism and metaphors. He combines sharp political analysis with compassion, optimism, romanticism, and sometimes despair. His themes are ever encompassing yet distinctly human: he wrote love poetry, poems about Anatolian villagers and rural life, poems about the everyday struggle of the worker, poems about life in prison, and in true internationalist fashion, poems dedicated to communist figures worldwide as well as a poem dedicated to the working class of neighbouring Greece – long a rival of the Turkish state. Yet, all his poetry is tinted with his distinctive “romantic communism” – his poems are nostalgic representations of the peasantry and proletariat of his country, devoted visions of the Anatolian countryside and intimate accounts of the struggles of the everyman, while also being ferocious exposes and critiques of the capitalist system.

The following poem, written while Nazim Hikmet was in prison, will perhaps comfort the reader and remind them to not only survive ,but also live and thrive in these times when global fascism and oppression is on the rise once more.

Some Advice to Those Who Will Serve Time in Prison

By Nazim Hikmet, May 1949

If instead of being hanged by the neck

You’re thrown inside

For not giving up hope

In the world, your country, and people,

If you do ten or fifteen years

Apart from the time you have left,

You won’t say,

“Better I had swung from the end of a rope like a flag” –

You’ll put your foot down and live.

It may not be a pleasure exactly,

But it’s your solemn duty

To live one more day

To spite the enemy.

Part of you may live alone inside,

Like a stone at the bottom of a well.

But the other part,

Must be so caught up

In the flurry of the world

That you shiver there inside

When outside, at forty days’ distance, a leaf moves.

To wait for letters inside,

To sing sad songs,

Or to lie awake all night staring at the ceiling

Is sweet but dangerous.

Look at your face from shave to shave,

Forget your age,

Watch out for lice

And for spring nights, and always remember

To eat every last piece of bread –

Also, don’t forget to laugh heartily.

And who knows,

The woman you love may stop loving you.

Don’t say it’s no big thing:

It’s like the snapping of a green branch

To the man inside.

To think of roses and gardens inside is bad,

To think of seas and mountains is good.

Read and write without rest,

And I also advise weaving

And making mirrors.

I mean, it’s not that you can’t pass

Ten or fifteen years inside

And more –

You can,

As long as the jewel

On the left side of your chest doesn’t lose its luster!

References and Further Reading:

Arslanbenzer, Hakan (2015). Nazim Hikmet: Human Scenes from my Homeland. Daily Sabah. Retrieved from https://www.dailysabah.com/portrait/2015/10/17/nazim-hikmet-human-scenes-from-my-homeland

Blasing, Randy, & Konuk, Mutlu (2002). Human Landscapes from my Country. New York. Persea Books.

Blasing, Randy, & Konuk, Mutlu (1994). Poems of Nazim Hikmet. New York. Persea Books.

Goksu, Saime, & Timms, Edward (1999). Romantic Communist: The Life and Works of Nazim Hikmet. New York. Palgrave Macmillan.

Onayli, Kutay (2014). Nazim Hikmet: A Loving Revolutionary. Vagabond Magazine. Retrieved from http://vagabondmagazine.org/nazim-hikmet-romantic-communism/