There is no existence more complicated, convoluted and rewarding than being a human being. We live within our own inventions: insulated homes, organized municipal communities, restaurants, the internet, language – so who would want to be anything else?

Now, across cultures relationships with land and animals vary, and since I cannot personally speak on the dynamics of indigenous peoples, or cultures outside of the white Western world, this article is largely geared towards us that live within and engage with Western and Eurocentric institutions and how they impact our concept of animals lives and their worth. I dare say the western lens has given our identities as human beings an ego, an ego that prevents us from seeing how our success impacts all the other beings that occupy the Earth with us. We call some of these beings “man’s best friend”; others we’ve hunted to extinction or genetically modified to the point of incapacitation. We are not kind to animals, and how kind we are depends largely on how they serve us: dogs and cats are domesticated to become pets, pigs and cows become food, ungulates become trophies, reptiles become handbags, and almost all animals become public, consumptive spectacles à la zoos, aquariums, museums. As a culture we have killed off innumerable species because they inconvenience our progress. We have decided that our bodies hold more value than others, that our minds hold more potential than others, and that our standards of efficiency and progress are superior to those of other species.

These acts manifest in how we collectively decide to consume, abuse, displace, and use other animal species for our own gain. Animals hold high cultural value in numerous societies around the world, but in the last two centuries under Western capitalism have been demoted to an extractive resource. The North American food industry is an appalling example of desensitization to animal suffering and worth as living things. This dates back to processes of colonial land enclosures and displacement of Indigenous communities and the invasion of many European species into the Americas’ ecological landscapes. We see not only the excessive sacrifice of animal lives but the sacrifice of thousands of acres of land to animal waste pits, corn fields and corporate farms that undermine small-scale subsistence farmers and communities. Where do the solutions lie? The academic rhetoric and grassroots application of these principals manifests in the movement of ecofeminism.

Ecofeminism aligns the oppression of animals with the exploitation of the land via colonialism, privatization, corporate farming, and animal industries like food, fashion, cosmetics and game. As per the article linked above, “the environment is a feminist issue.” Ecofeminism seeks to place all this research in a common thread of theory that conceptualizes animals and the natural world as a subjugated class under a white patriarchal agenda whose issues exist alongside women, people of colour, trans communities, and disabled communities. It recognizes that rhetoric similar to that which is employed to subjugate these communities has also been/is applied to animals. What is crucial to the logic of this subjugation is the idea that characteristics like intelligence, productivity, innovation and utility can only be applied to humans and human invention. Actively conceptualizing animal lives as inferior to human beings because of potential they cannot posses is a tool of species essentialism.

Species essentialism, like gender essentialism and racial essentialism, presumes the identity, capabilities and potential of individuals in a community according to prescribed beliefs about them based on incurable characteristics, species in this case. Species essentialism erases the agency of animals and right to a life without human interference.

You can refer to a previous Social Justice Synonyms article on speciesist terms, using animals as negative descriptors is not only incredibly disrespectful, but confirms beliefs that justify the subjugation of animals because they are less than, or stupid, or dirty. Many animals are quite self-aware of their hygiene, their emotions, and their place within a community. Pigs even have their own systems of communication. However, this shouldn’t have to be proven before one makes the decision to become an ecofeminist, because all forms of animal intelligence deserve life. Animals do not need to have human-like characteristics for us to feel compassion for them. Yet within Western culture we continue to alienate their autonomy from their fulfillment of our needs.

This fetishization of animal bodies and labor is seen all over media, from “Got Milk?” commercials of men gyrating on cows to fast food restaurants framing their quarter-pounder as a delicious product devoid of the body it was made from, to the consumerist elitism of alligator purses and shoes.

These attitudes manifest in our language e.g., calling people bitches, and drawing negative comparisons to pigs and cows. There has also been much prejudice comparing people of African descent around the world to monkeys and likening Indigenous peoples to animalistic savages. These racist derogatory likenings have manifested in illustrations, advertisements, Disney cartoons and common consciousness. For example, this past summer at the World Cup in Brazil, bananas were thrown in the arena at black football players.

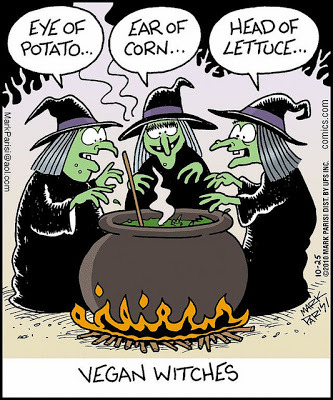

Now, if you haven’t already guessed, I’m a vegan, which means no animals or animal by-products go in my body. I eat vegan, wear vegan (faux fur and pleather only!) and advocate for the lifestyle whenever I can. It eliminates a lot of restaurant options when I go out and exasperates my mother to no end, but it’s what I can do to take money away from industries that not only kill animals, but also contribute to the destruction of the environment in which they live. My digestion, skin and energy are all markedly better than they were before I transitioned to a vegan diet over a year ago. But I hesitate to hyperbolize how much better I feel, ethically and physically, because veganism isn’t always a cheap, accessible lifestyle. While I’m always game to talk about the personal positives I’ve found in being vegan, it’s not for everyone. I am fortunate enough to have access to lots of affordable produce and foodstuffs and that my body can handle a plant-based diet. Vegans can be pretty defensive (we do get asked, without fail, “how did you give up cheese?” like every time we tell someone we’re vegan) but they’re not always right. If you care to, see how many times you consume an animal product in a day. Maybe you’ll find you want to make some changes.

One of the greatest powers we wield over animals is the power of the oral and written language. As a species we’ve developed a thousand ways to communicate our feelings, so why is it so hard to recognize that in animals? Animals don’t have the access to literature we’ve accumulated, or the ability to produce their own and inform us of how they feel. As people, we know better. We know what slaughterhouses look like, what skinning looks like, what cosmetic testing and puppy mills and zoos look like, so why do we let these industries persist? The representation of animals and social conceptualization of animals are linked: we cannot respect their livelihood while we co-opt their identities as slurs. Animals do not know how to replant forests or shut down factories. Our responsibility for animal life began when we took responsibility for their death.

Special thanks to to milo and alexis for unbeknowingly letting me into their world.

Amelia is an aries with a shrinking stomach and half a bachelor’s.