Certain aspects of Remembrance Day make me uncomfortable, and I don’t think I’m alone in this.

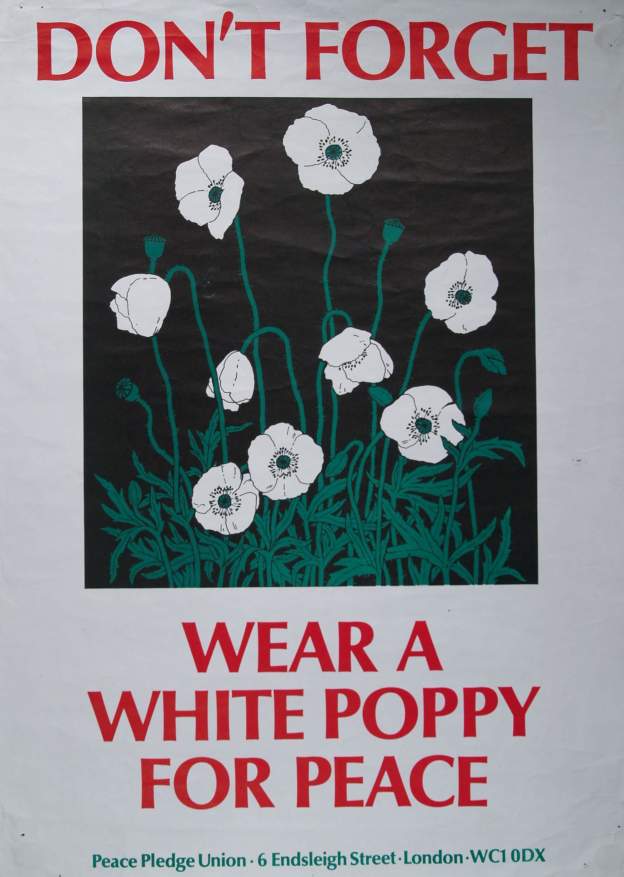

The white poppy (sometimes called the peace poppy) is worn as an alternative to the red poppy, and is meant to ensure that remembering past conflicts doesn’t involve glorifying or simplifying war. Traditional Remembrance Day ceremonies honour the victims of war within certain nationalistic frameworks, and I find that problematic because it erases the struggles and sacrifice of those who are excluded from this nationalist project. Along with this comes a sort of militarism that I think works against the greater goal of these ceremonies; to make sure that these sacrifices don’t need to happen and that we should work towards ending war.

This year, I’m wearing the white poppy because it more closely aligns with the way I choose to remember the victims of war.This article is not meant to be a critique against remembering those who fought in past conflicts but to examine some features of this annual day of memorial: it is meant to call attention to what we remember, and who we remember (or more specifically who we don’t remember) on November 11.

The recent reports which revealed that Canadian inmates assembled 2.4 million red poppies for the Canadian Royal Legion this year might be a good reason to start looking into the standard Remembrance Day narrative about the sacrifices made in “fighting for our freedom.”

How can we remember war while acknowledging colonial violence both at home and abroad? How can we make sure that Indigenous sovereignty is respected and that Remembrance Day doesn’t mean discounting Indigenous veterans as it did at last year’s Remembrance Day parade in Ottawa? What about the Indigenous warriors who protect our environment against multinational oil companies? They certainly aren’t mentioned in memorial ceremonies I attended growing up. How can we talk about the colonial policies of European states and the war that was waged against colonized people across the world? How can we work towards a Remembrance Day that includes respecting the victims of colonial oppression? I’m not arguing that the white poppy is the solution these problems, but it’s a way of moving the conversation towards peace and beginning to talk about alternative ways of looking at war memorial.

A lot of the significance of the white poppy, for me at least, has to do with its origin. The white poppy was first printed around 1933 by the Co-operative Women’s Guild in Britain, a group organized around working class labour issues and issues pertaining to women. This was a group of individuals who had not participated directly in fighting but had served as nurses and in support position during conflict, and had seen the impact war had on returning soldiers.The Co-operative Women’s Guild was a civilian group who were able to gauge the effects war had on society as a whole.

The white poppy is rooted in the idea that everyone affected by war should be remembered, including civilians who became (and continue to become) the “collateral damage” of global politics. The movement aims to acknowledges that war is complex and shouldn’t be placed within a rhetoric of heroism and nationalistic pride.

The Peace Pledge Union is a pacifist group and one of the biggest organizers of this white poppy distribution. They write: “The white poppy was not intended as an insult to those who died in the First World War – a war in which many of the white poppy supporters lost husbands, brothers, sons and lovers – but a challenge to the continuing drive to war.” Through the work of the Peace Pledge Union and other organizations, the white poppy is re-centering the Remembrance Day conversation around peace.

Publicly, there has been some opposition to the white poppy. While the Royal British Legion has no opposition to the white poppy, the Canadian Royal Legion has shown some opposition in the past, but oddly enough, it was mostly for trademark reasons. Sun News and the Conservative Party Minister of Veterans Affairs have also come out against the white poppy as well.

Remembrance Day is focused on nationhood and emphasizes military solutions. Remembering those who have lost their lives in war is important, but I will not apologize for anger directed at politicians who could not resolve conflicts through diplomacy and who made the decision to send soldiers into battle. As others have argued before me, there’s a certain degree of hypocrisy in Stephen Harper wearing the red poppy a mere 9 days after Canadian bombs fell in Iraq.

Being able to position this memorial holiday within the proper historical and contemporary context is key here: to remember that although this year marks the 100th anniversary of the beginning of World War I, a conflict that may seem like it was a long time ago, the Canadian government is still very much involved in military action today and therefore benefits from implicit narratives of militarism. On Remembrance Day, we need to question what our government has been doing to promote peace.

We also need to remember that those who fought in the world wars often did not do so on their own accord (conscription), and were essentially victims to the whims of imperialistic land grabs and the ruling class as a whole.

Nationalistic campaigns of propaganda and manipulation aimed at gaining support for military action and recruiting soldiers were deployed on a massive scale for both world wars. Soldiers who were recruited and drafted (who gets exempted from conscription? Definitely not the low-waged factory worker) by governments have traditionally come from the working class, and often recruitment came with a temporary injunction over racial inequality: a valuing of marginalized bodies when these bodies could be holding a gun and serving on the front lines.

The rhetoric of the red poppy diminishes or often completely omits the sacrifices of women, Indigenous peoples, immigrants, people of colour, and all of those who do not fall into the Ideal Canadian Soldier: the young fit white male – the abstracted body that dominates the representation of sacrifice at memorials and in Remembrance Day speeches. Tokenizing women on Remembrance Day is not going to do the trick either.

For me, the question is not about remembering or not remembering: it is clear that the victims of war should be remembered and honoured. But to me this is about finding a new way to remember, one that pays respect to all those affected by war while remaining critical of the historical and ongoing injustices perpetrated by Canada, and most importantly, one that calls for an end to all war.

Special Thanks to Urooba Jamal for their assistance with this piece.